Extraordinary weather event

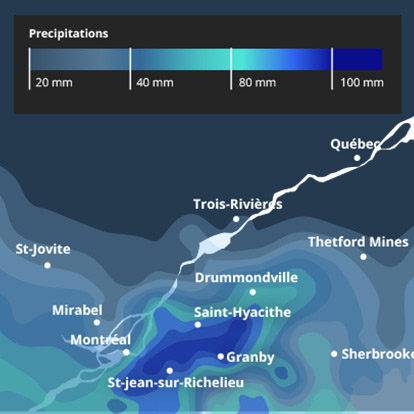

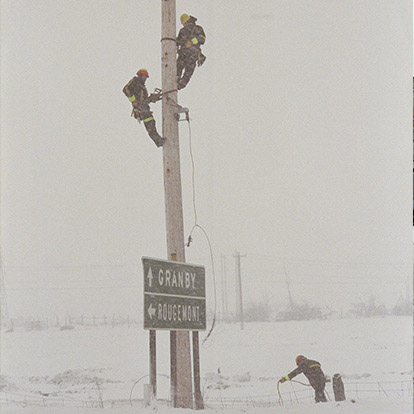

I have to see my boss in five minutes. I’ve got bad news. The first storm has deposited 10 to 20 mm of ice.

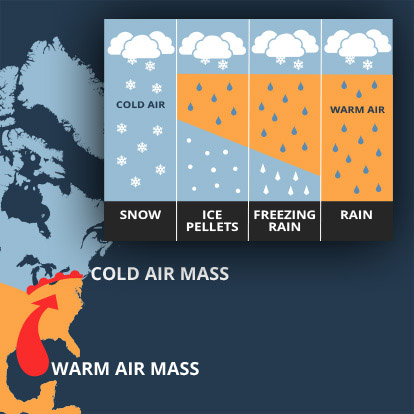

The situation wouldn’t be as critical if Mother Nature had left it at that. But all the analyses I’ve done of the most recent satellite images and weather models lead to the same conclusion: two more low-pressure systems are on their way to Québec. But I have no idea if they’ll bring ice pellets or freezing rain. What are we going to tell all the people shivering in the dark?