Important reminder

In the event of a flood, contact your municipality. They will advise the Ministère de la Sécurité publique du Québec, which coordinates all flood-related activities.

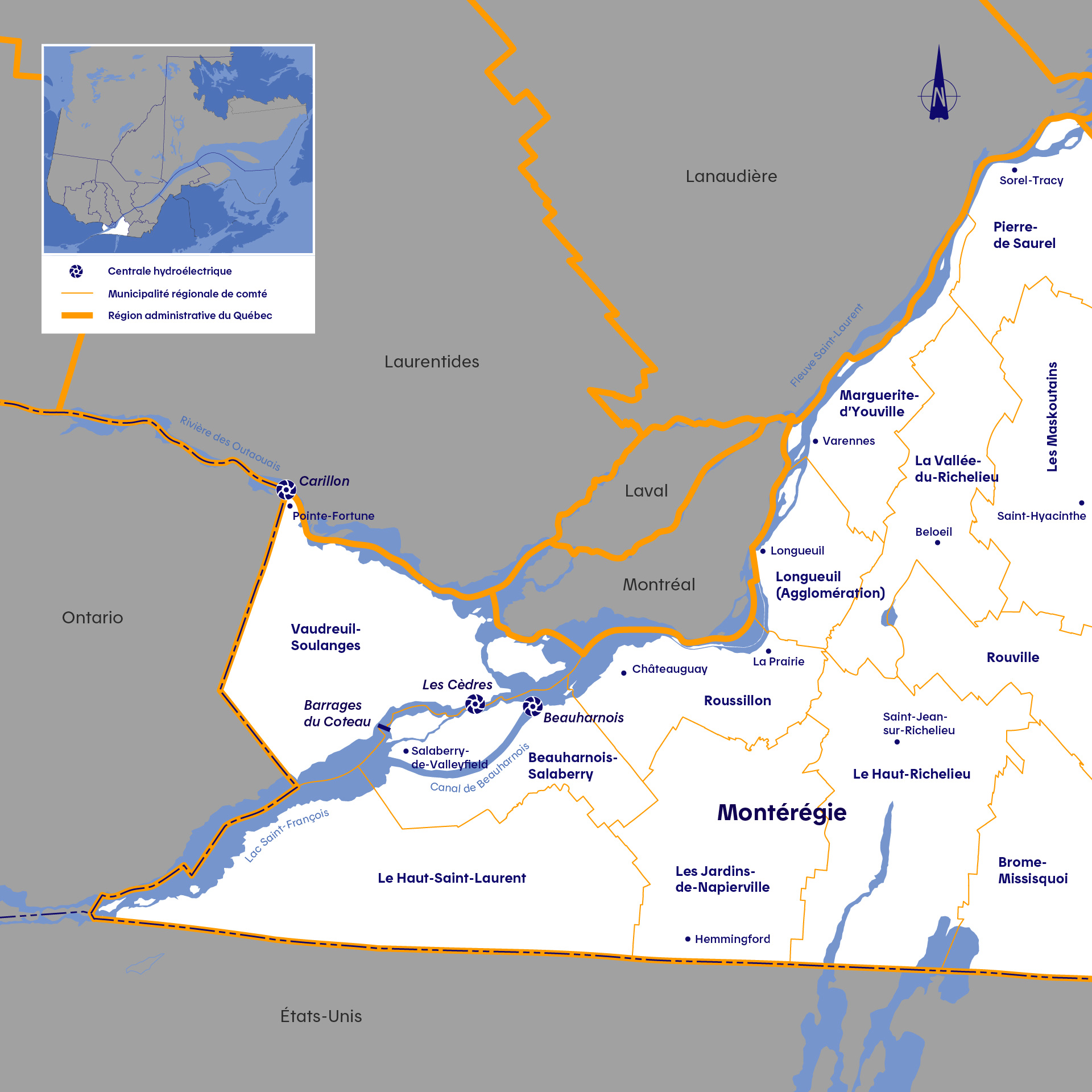

Montérégie

Reducing spring flooding on the Saint-Laurent and Outaouais rivers: A team effort

In the Montérégie region, Hydro-Québec operates hydroelectric generating stations in two watersheds: the Outaouais (Ottawa) river system and the Saint-Laurent (St. Lawrence) river system. These watersheds are home to Carillon, Beauharnois and Les Cèdres generating stations, which are all run-of-river stations. Because they do not have reservoirs, these generating stations cannot store water the way reservoir generating stations can.

Role of the Ottawa River Regulation Planning Board

Several large rivers flow into the Outaouais, which drains a watershed of 146,000 km2 and covers a distance of 1,120 km, from Abitibi-Témiscamingue to Montréal. These inflows make the Outaouais a significant tributary of the Saint-Laurent near Montréal. Hydro-Québec is not the only operator of reservoirs and generating stations in the Outaouais watershed. Managing the water levels and flows in the Outaouais is a collaborative effort between partners. Every drop of water in the river is monitored by the Ottawa River Regulation Planning Board (ORRPB).

(ORRPB).

The ORRPB is made up of all the agencies that participate in managing the Outaouais watershed: the Ministère de l’Environnement, de la Lutte contre les changements climatiques, de la Faune et des Parcs du Québec, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry of Ontario, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Public Services and Procurement Canada, the Canadian Coast Guard, Ontario Power Generation and Hydro-Québec.

Visit the ORRPB website to track the hydraulic conditions of the Rivière des Outaouais.

A tool that identifies flows and water levels

We are installing measuring instruments on rivers and reservoirs where we operate dams and generating stations. They provide flow, water level and meteorological data. This data is available to you through a simple tool, which can provide information about flows on rivers and water levels in reservoirs.

Learn more about the Tool

We reduce spring flooding thanks to our reservoirs. Find out how.

From December to March, Hydro-Québec gradually empties its reservoirs located in the northern Outaouais and Abitibi-Témiscamingue regions. When the spring thaw begins, they contain almost no water. From early April to early June, we fill the reservoirs to almost capacity and store the water as long as possible to limit inflows to the Outaouais and the Saint-Laurent rivers, which are already swollen with water from the surrounding watersheds. However, the reservoirs only have access to 40% of the water inflows. The remaining 60% are from watercourses that do not run through our reservoirs; they flow freely and cannot be retained.

All the generating stations located on these watercourses are run-of-river and do not have reservoirs to hold water. The only facilities that impact the magnitude of the spring flood are the reservoirs located north of the watershed, which we manage in collaboration with our partners.

For more information on the Rivière des Outaouais watershed, visit the Ministère de l’Environnement, de la Lutte contre les changements climatiques, de la Faune et des Parcs du Québec (web page in French only).

(web page in French only).

Watch our expert explain how Hydro-Québec contributes to managing spring runoff along the Fleuve Saint-Laurent.

Did you know?

Carillon generating station, which is located at the foot of the Rivière des Outaouais watershed, is a run-of-river generating station.

It does not have a reservoir and therefore cannot store spring flood water. During flood periods, the spillway discharges the excess water.

If the spillway gates were closed at the peak of the high water levels due to spring flooding, the water would spill over the facility within a few hours!

Hydro-Québec does not manage the level of the Saint-Laurent. The ILO‑SLRB does.

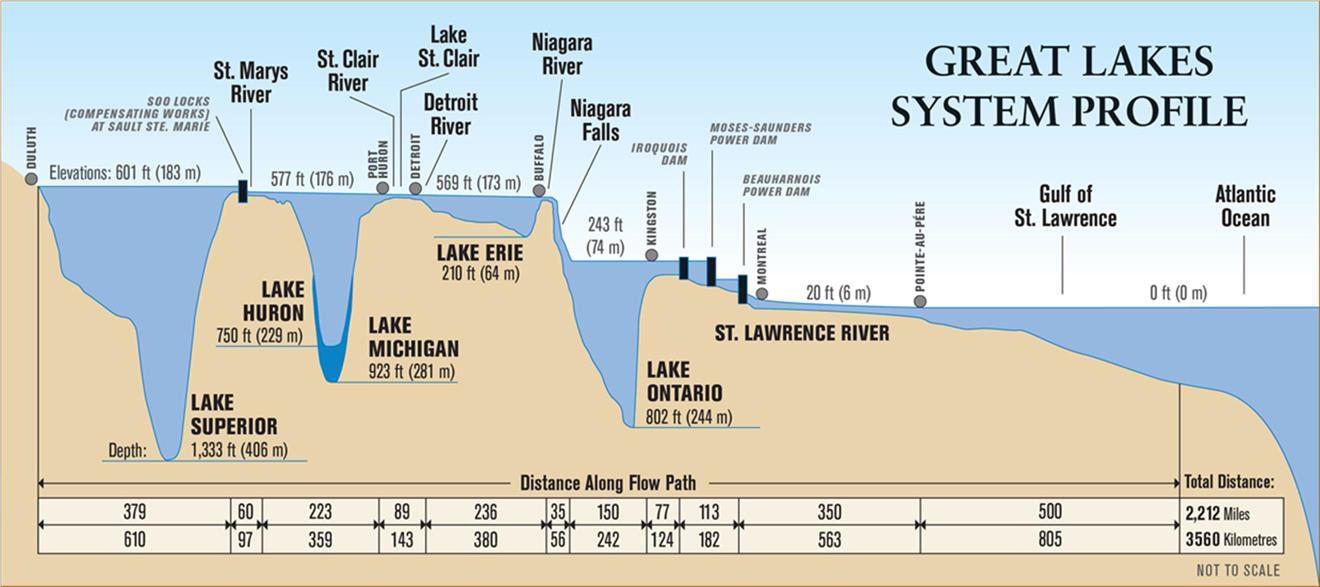

The inflows to the Saint-Laurent are managed in conjunction with the International Lake Ontario – Saint Lawrence River Board (ILO-SLRB), which ensures that the regulation of the levels and flows in Lake Ontario and the Saint-Laurent complies with the legal requirements of the International Joint Commission (IJC). The mandate of the ILO-SLRB covers the entire watershed, from the Great Lakes to Lac Saint-Pierre and to the Montréal archipelago area.

(ILO-SLRB), which ensures that the regulation of the levels and flows in Lake Ontario and the Saint-Laurent complies with the legal requirements of the International Joint Commission (IJC). The mandate of the ILO-SLRB covers the entire watershed, from the Great Lakes to Lac Saint-Pierre and to the Montréal archipelago area.

The ILO-SLRB works daily with numerous stakeholders, including the St. Lawrence Seaway Management Corporation, the Canadian Coast Guard, U.S. and Ontario hydropower producers and Hydro-Québec.

Hydro-Québec has a direct role in managing the Beauharnois–Les Cèdres hydropower complex, located in the west of the Montérégie region, but does not manage the level of the Saint-Laurent. We work with the ILO-SLRB to safely manage the ice near the complex, which consists of run-of-river generating stations and therefore cannot retain water. For example, Beauharnois generating station receives the water that comes through the Beauharnois canal, runs it through turbines and then redirects it toward Lac Saint-Louis.

During the spring thaw, the members of the Ottawa River Regulation Planning Board (ORRPB) and the ILO-SLRB work together to reduce the inflows to the Montréal archipelago area. Since Hydro-Québec operates the two generating stations closest to the archipelago, our experts play a key role in this aspect of flood management every spring.

(ORRPB) and the ILO-SLRB work together to reduce the inflows to the Montréal archipelago area. Since Hydro-Québec operates the two generating stations closest to the archipelago, our experts play a key role in this aspect of flood management every spring.

Frequently asked questions

Why can’t Hydro-Québec hold back water upstream of the Coteau dams on the Saint‑Laurent?

Why has the flow in the Saint-Laurent been higher since 2017?

How does the emptying and filling of basins along the Saint-Laurent work? Would it be possible to have water year‑round?

On the Rivière des Outaouais (Ottawa River), could more water be held back by the facilities located in the north so that less water flows to the south?

Questions on how Hydro‑Québec facilities are managed? Write to us at Affairesregionales@hydroquebec.com.